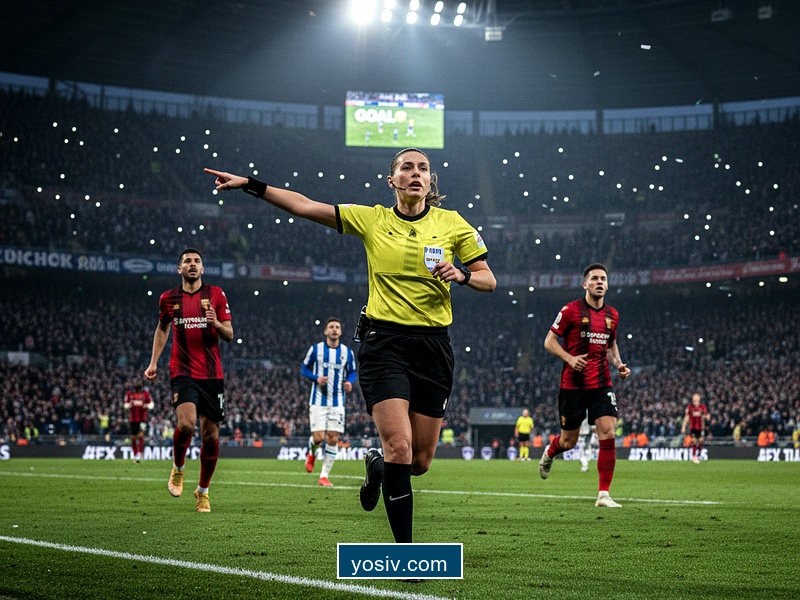

Watch the feet. Forget the flag for a moment and watch the feet. In the scouting world, we often talk about "hip decoupling"—the ability of a winger to run one way while facing another. But the most technically demanding lateral movement on a Premier League pitch isn't being performed by Mohamed Salah or Bukayo Saka. It is being performed by the person patrolling the touchline in black.

The Assistant Referee (AR) is the game’s most misunderstood athlete. And make no mistake, they are athletes. If we were to draft an AR based on a scouting dossier, we wouldn't look for someone who knows the rulebook. Any fool can memorize Law 11. We are looking for a physiological anomaly capable of sprinting 30 kilometers per hour while sidestepping, possessing the peripheral vision of a fighter pilot, and the mental resilience to ignore 50,000 people questioning their parentage.

To understand what makes an elite AR, you have to strip away the uniform and look at the biomechanics. The modern game, with its obsession with high lines and pressing triggers, has transformed the role from a ceremonial position into a high-performance gauntlet.

The Biomechanics of the "Crab"

The fundamental movement pattern of an AR is unnatural. Humans are designed to run forward. The AR must run sideways, a movement known in coaching circles as "shuttling" or "crabbing," while maintaining a sprint velocity that matches elite center-backs. The requirement is absolute: the shoulders must remain square to the pitch to maintain the "offside line," but the hips must allow for lateral propulsion.

"The sheer eccentric load placed on the adductors and the IT band during 90 minutes of high-intensity shuttling is enough to end a normal runner's career in a month."

When I scout a fullback, I look for recovery speed. When assessing an AR, I look for the transition from the "crab" to the sprint. The elite AR stays side-on for 90% of the match. However, when a counter-attack breaks—think of a clearance over the top for a striker like Erling Haaland—the AR must execute a "drop-step," pivoting 90 degrees to sprint forward, all while keeping their head on a swivel. If this pivot takes 0.5 seconds too long, the angle is lost. The parallax error kicks in. The call is blown.

This is where the injury profile mirrors that of a hockey goaltender more than a soccer player. The groin and hamstring are under constant, erratic tension. They don't get the luxury of a rhythmic stride; their movement is dictated by the chaotic movement of the defensive line.

The Optical Science: Defeating the Flash-Lag Effect

The average fan screams "blind" when a tight offside is missed. A neuroscientist would call it the "Flash-Lag Effect." This is a visual illusion where a moving object (the striker) is perceived to be ahead of its actual position compared to a stationary or slower-moving object (the defender) at the exact moment of a "flash" (the ball being kicked).

An elite AR isn't just watching; they are processing two distinct focal points simultaneously. This is the scout's definition of "split attention." They must fix their foveal (central) vision on the offside line—specifically the second-to-last defender—while using auditory cues (the thud of the boot) to determine when the ball is played.

Amateurs look at the ball. Pros look at the line. The very best ARs have trained their brains to suppress "saccadic masking"—the momentary blindness that occurs when the eyes jerk rapidly from one point to another. If an AR glances at the passer and then back to the line, they are effectively blind for 50 milliseconds. In the Premier League, 50 milliseconds is half a yard. The elite technique requires a rigid neck and a reliance on peripheral motion detection that borders on the supernatural.

Tactical Empathy: Reading the Pressing Triggers

We talk about game intelligence in midfielders, but an AR needs a higher tactical IQ than most players. Why? Because they must anticipate the defensive line's movement before it happens.

Consider the "offside trap." An AR cannot react to the defenders stepping up; they must react to the *trigger* that causes the step up. If a team like Aston Villa plays a high line, the AR is essentially playing left-back. They are watching the center-back's body shape. Is his weight on his back foot? He's dropping. Is he leaning forward? He's stepping.

Historically, this positioning has evolved significantly. In the days of Sir Stanley Rous, who formalized the Diagonal System of Control in the mid-20th century, the game was slower. The lines were deeper. Today, with the compression of space, an AR might make 400 distinct explosive movements in a game. If they don't understand the tactical setup—if they don't know that Liverpool plays a high line while Everton might sit in a low block—they will be permanently out of position. They are scouting the tactics in real-time.

The Invisible Tech: The Bip and The Flag

The flag itself is not just a piece of cloth; it is a communication device with heft. The grip mechanics matter. You will notice elite ARs switch the flag to the hand nearest the touchline during play. This "hand-switching" is a subconscious drill, ensuring the flag is never obstructing their view of the pitch.

But the real unseen work happens through the electronic buzzer system integrated into the handle. This was a game-changer introduced alongside comms units. When the flag button is pressed, the main referee gets a vibration on their arm. It creates a binary language: a short 'bip' for a foul, a sustained signal for offside.

This adds a layer of manual dexterity to the physical demands. Imagine sprinting at full tilt, tracking a striker, maintaining the offside line, and simultaneously manipulating a button with your thumb to signal a foul that the center ref might have missed behind their back. It is multitasking under extreme duress.

The VAR Paradox: Muscle Memory vs. Protocol

The introduction of VAR has introduced a cruel psychological twist to the profession: the "delayed flag." For 100 years, the instinct was immediate. See infringement, raise flag. Now, we are asking these officials to override their central nervous system.

They must recognize the offside, mentally log it, allow the play to conclude (sometimes for 10-15 seconds), and *then* raise the flag. This requires a terrifying level of cognitive dissonance. They must adjudicate the play as illegal while officiating it as if it were legal. From a scouting perspective, this measures "composure under ambiguity."

If they flag too early on a tight call, they kill a potential goal and endure a week of media slaughter. If they wait too long and a player gets injured in the "dead" time, they are liable. It is a no-win scenario that filters out anyone lacking supreme mental fortitude.

The Verdict

The next time you see an AR keep their flag down on a razor-thin margin, do not credit luck. Credit the eccentric strength of their glutes holding a crab stance at high speed. Credit the suppression of the Flash-Lag effect. Credit the tactical study of the defensive line's triggers.

We scout players for millions of dollars based on their ability to find space. Perhaps we should possess the same reverence for the men and women whose entire career depends on their ability to define it. They are the gatekeepers of the game's geometry, performing a high-wire act where the only net is a pixelated line drawn by a computer miles away.